When I was still a teenager – summer brave, full of sport, hot and bold – I hitchhiked from Lithuania to Armenia and back again. Outbound via the former Soviet Union and the Caucasus; home via Turkey and the Balkans.

Time rich and cash poor, I took risks I wouldn’t today. All the same, my gambles paid off and I look back on that adventure fondly.

The journey was filled with comparisons and contrasts. Some things, like being invited in basic Russian to squeeze into a crammed Lada Riva, remained almost constant from country to country. Others, like the landscapes and local delicacies, evolved with every new ride.

When I found myself back in Istanbul last month for the first time since my hitchhiking days, I was again struck by these contrasts. Here I was with my colleague, Daniel Stander, a guest of the United Nations, discussing disaster risk reduction financing with the finance ministers of those countries through which I’d once hitchhiked. And here I was, marvelling afresh at the cultural, political, economic and geographical diversity of a vast region which yet shares so much.

Resilience Exists at All Scales

The UN’s Development Programme (UNDP) takes a regional approach across around 20 countries in Eastern Europe, the Balkans, the Southern Caucasus and Central Asia.

And with good reason.

Despite its diversity, each country in the ECIS region faces three common challenges: hazard seems to be rising, exposure is increasingly concentrated and the finance and protection gaps remain high.

The upshot: communities at risk, with governments unable to fund disaster recovery.

The record Balkan floods of 2014 vividly illustrate this. Extratropical Cyclone Tamara claimed more than 85 lives and displaced over half a million people across five Balkan countries. In three days of rainfall and landslides, Bosnia & Herzegovina experienced damage equivalent to 15 percent of its GDP, not to mention panic that 120,000 unexploded landmines might be on the move. A national state of emergency was declared by the Serbian government, which took a €227 million emergency loan from the World Bank, on top of over €100 million in aid from donor nations.

In the last ten years, there have been 314 disasters in Eastern Europe and the CIS, resulting in more than 60,000 people killed, 11,000,000 people affected and physical damage alone of US$25 billion.

The Balkans are not alone. Georgia and Tajikistan find themselves in an unenviable global top ten list: countries with the highest average annual loss relative to GDP.

Indeed, during my teenage travels, I experienced first-hand the effects of natural disaster on a community. Following an earthquake in Southeast Turkey (and the example of aftershock-fearing locals), I opted to sleep outside. These rural communities had neither viable homes nor insurance to rebuild.

The need for resilience, it seems, exists at all scales – from the farmer to the finance minister. And it is this need which underpins the UNDP’s strategic objective “to chart risk-informed development pathways to prevent crises”.

One Size Does Not Fit All

With hard-earned development gains at the mercy of border-crossing seismic faults, rivers and extreme weather patterns, what can be done to shore up the social and economic resilience of the region? Given that a one per cent increase in insurance penetration reduces taxpayer burden by one fifth, how can risk financing promote a culture of sustainable development?

Much ground was covered to this end during the Istanbul workshop. The full read-out can be found here.

One solution in particular gained traction: sovereign and sub-sovereign catastrophe pools, backed by parametric capital.

Turkey has been securitizing earthquake risk in the alternative markets since 2013. On an individual basis however, many ECIS nations may not yet have the technical or financial capacity that a catastrophe bond requires. Discussion therefore turned to multi-national sovereign risk transfer.

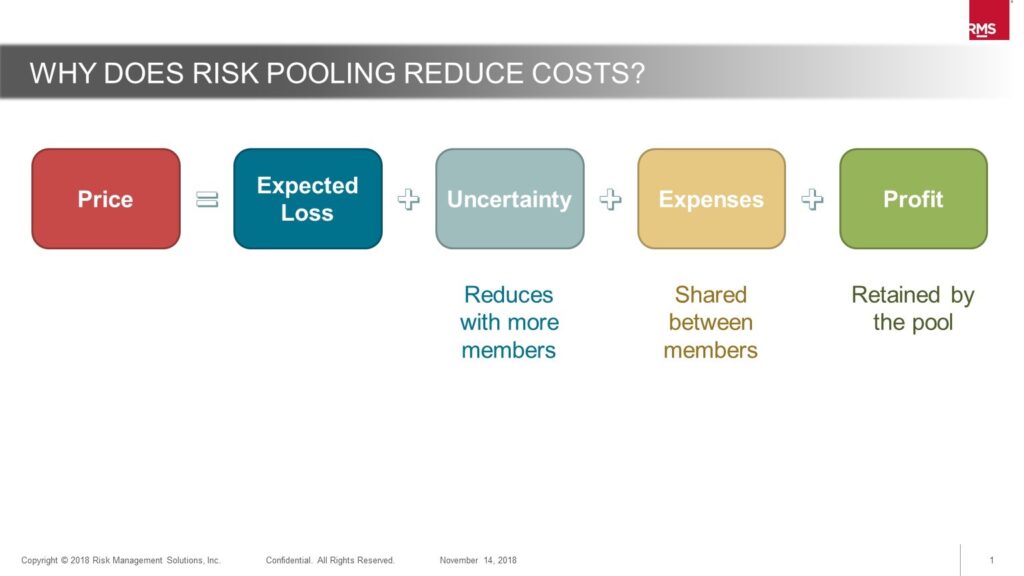

This approach, which has proven its worth in the Caribbean, Latin America and Africa, has four advantages:

- Uncertainty reduces with more members

- Expenses are shared between members

- Premiums reduce with geographic and peril diversification

- Any profits are retained by the pool

The lesson: combining exposure into regional pools can offer an efficient approach to begin modelling and financing risk.

A supranational pool in the region would furthermore appeal to ILS investors hungry to diversify into relatively uncorrelated geographies. Indeed, Turkey’s issuances demonstrate that there is appetite and capacity for both ILS and sophisticated parametric triggers.

For such pools to get off the ground, experience suggests there needs to be a galvanizing force. The countries participating in this year’s US$1.36 billion, Pacific Alliance cat bond are united by a shared language and trading bloc. In the case of the Caribbean’s CCRIF, it was the collective experience of Hurricane Ivan that spurred political action.

Of course, differences in political will, regulations and languages may present challenges for this region. That said, eleven of the ECIS countries share a common history as former Soviet states. Furthermore, eight are today members of the Commonwealth of Independent States and participate in the CIS Free Trade Area. This may help the establishment of a sub-regional risk pool.

Modelling + DRR + DRF = Sustainable Development

Whilst catastrophe bonds provide an effective solution to cover residual risk, they are not a silver bullet. Much can be done to reduce the underlying exposure. The workshop therefore correctly explored various adaptive measures, such as resilient urban planning, tactical retrofitting, smart flood barriers and nature-based defenses.

The upside is twofold. First, the right interventions today can reduce the frequency and severity of the physical, social and economic impacts from future disasters. Second, resilient measures also reduce the cost of residual risk transfer. Indeed, today’s more innovative risk financing solutions combine disaster risk financing (DRF) with disaster risk reduction (DRR), to incentivise, for example, the enforcement of safer building codes.

Irrespective, however, of whether the region moves forward by physical adaptation, by financial transfer or by both, one criterion is clearly foundational: a deep understanding of the risk. As Gerd Trogemann, manager of the regional UNDP hub, put it, “development cannot be sustainable if it is not risk-informed”. And if you can’t measure it, you can’t finance it, especially when investor appetite is fed by probabilistic characterizations of risk and return.

Fit-for-purpose analytics are vital. Governments need to understand – and prepare for – the full range of potential scenarios, especially the devastating tail events that are often missing from the historical record.

Municipalities cannot afford to wait for a disaster to catalyze investments in resilience. Rather they should quantify the cost of inaction to reveal the hotspots of risk and stimulate ex-ante action.

Many ECIS nations are at this crucial juncture in their DRR financing journey. Just as I availed myself of local expertise during my younger, hitchhiking days, so I hope the ECIS nations will turn to experts for technical guidance along the way. Doubtless the UNDP has a vital role to play — convening, wayfinding and catalysing action across national borders.

And just as my youthful adventure across ECIS played an important role in my personal development, so risk – and the management thereof – is inseparable from the region’s sustainable development.

Faced with growing challenges, the time is now for governments to adopt tried and tested #ResilienceFinance strategies. Inaction will lead to disaster – and those most in need will continue to be those least able to pay.